What is Lyme disease?

Getty Images

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection. It often causes a rash and can also cause mild symptoms that include fever, headache, and fatigue, which can be treated with a short course of antibiotics. But Lyme disease can become serious, especially if not treated early.

The condition is named for Lyme, Connecticut, where a cluster of cases was first described in 1977. Despite its name, Lyme disease has been reported in every U.S. state except Hawaii. Once thought of as a “woods of New England” problem, if you spend time outside, you should understand Lyme disease. The CDC estimates that 476,000 Americans are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year — that’s more than the number of Americans diagnosed each year with breast cancer and colorectal cancer combined.

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia (you might also see it as Borreliella), a spiral or corkscrew-shaped bacteria known as a spirochete. There are several species of Borrelia. Borrelia burgdorferi is the most common one in the United States; Borrelia mayonii exists in the U.S. as well. Lyme infection also occurs in Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world.

How can you get Lyme disease?

Lyme disease bacteria is spread to humans through the bite of an infected black-legged tick. Ticks bite humans and animals to feed on their blood. While having this blood meal, an infected tick can release Borrelia into the body.

“If the basics of Lyme disease had been available to me when I first got it, then just knowing how to treat it and how it might progress would have been very helpful.”

Lyme Disease Patient Experience Survey Respondent

Male, 64, Dublin, CA

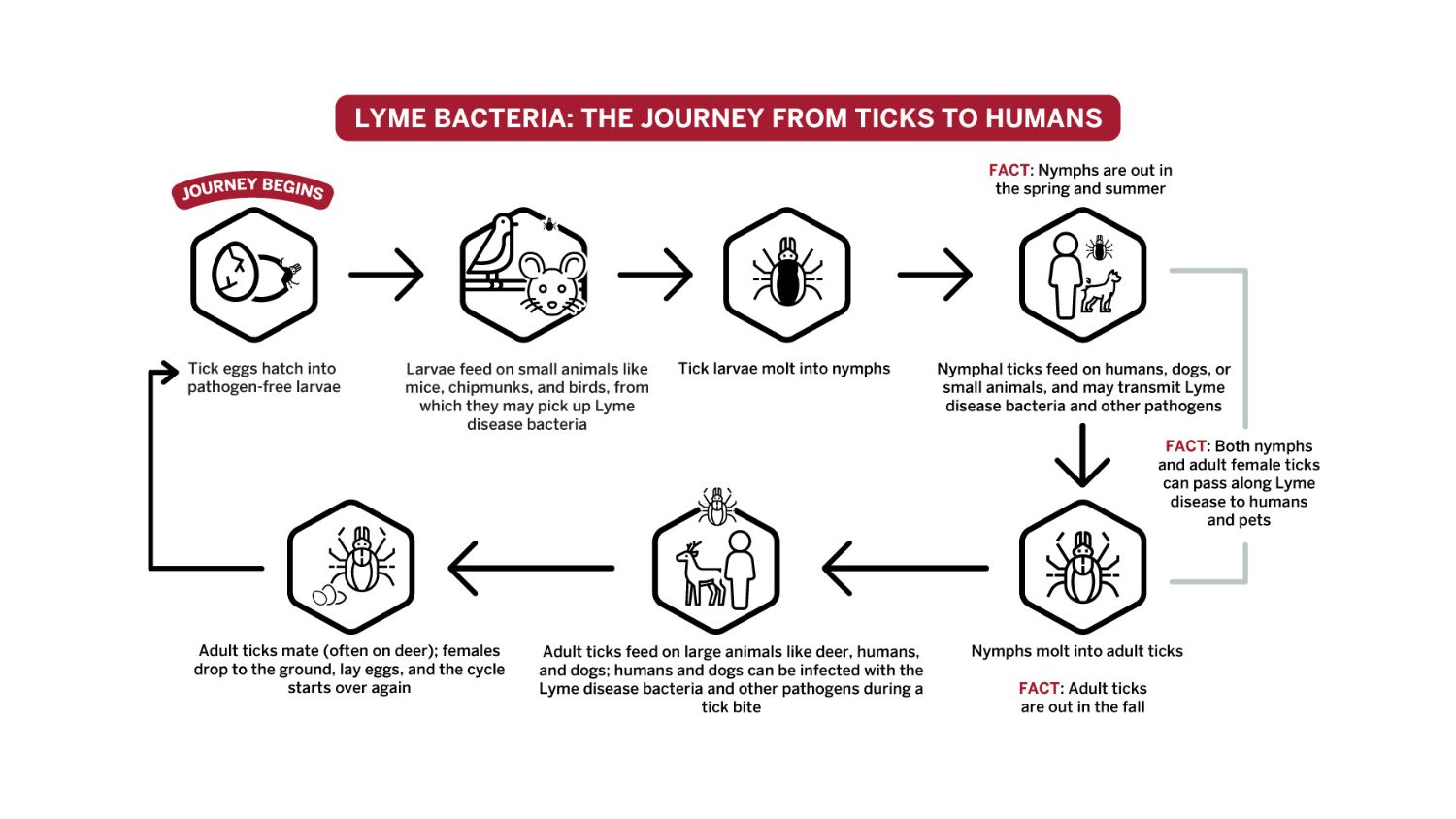

How do Borrelia bacteria make their way into ticks and humans?

Humans, ticks, and Borrelia spirochetes are players in a complex pathogen-vector-host relationship:

- Ticks pick up disease-causing germs (pathogens), including Lyme disease bacteria, while feeding on mice, birds, chipmunks, shrews, and other small animals (hosts).

- The ticks then become carriers (vectors) of those disease-causing pathogens, and can pass them on to new hosts — including humans and pets — when they bite them for their next blood meal.

Harvard Medical School

Understanding ticks

Ticks are tiny, blood-sucking bugs. They are arachnids (like spiders), not insects, and they do not have wings.

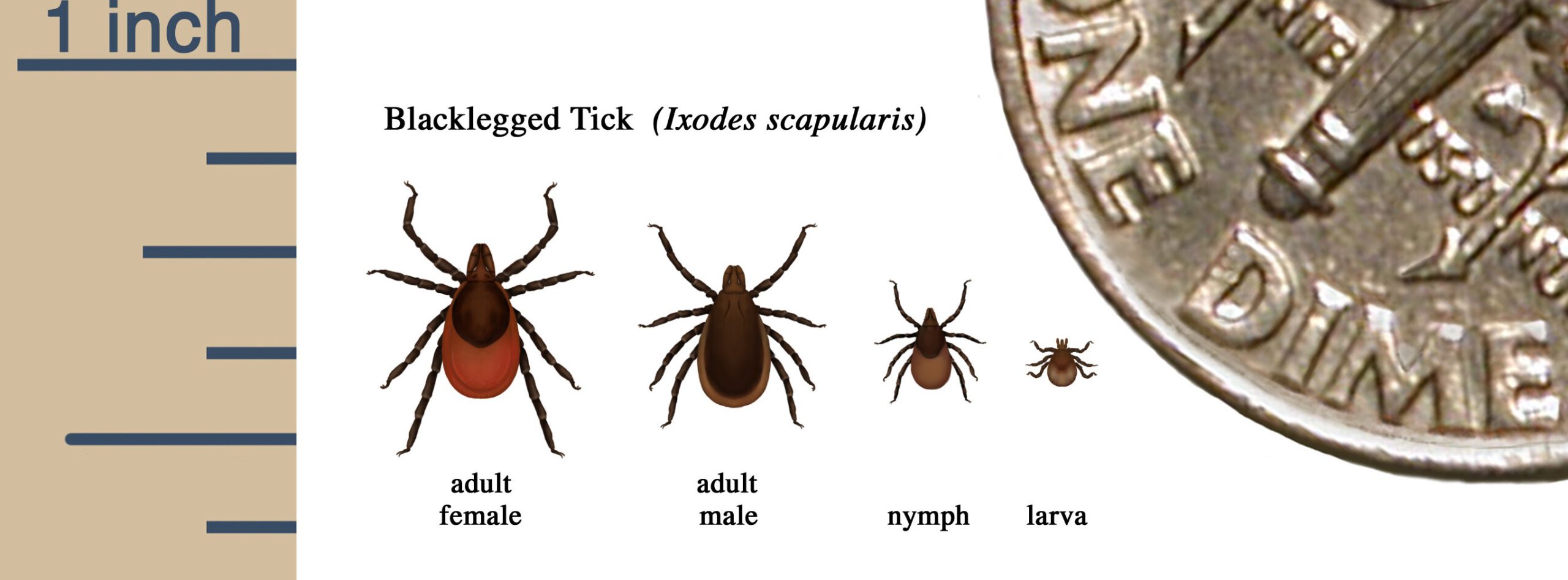

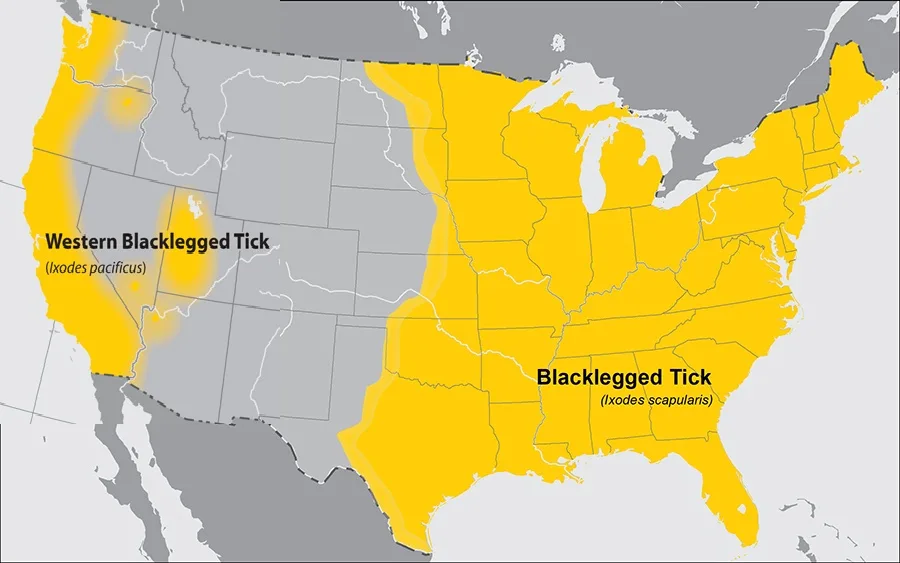

There are many types of ticks. Lyme disease is spread by black-legged ticks (“deer ticks”). The scientific name of black-legged ticks in the Eastern U.S. is Ixodes scapularis. Those found in the Western U.S. are called Western black-legged ticks, or Ixodes pacificus.

Black-legged ticks go through four life stages: egg, larvae, nymph, and adult.

CDC

What do ticks look like?

Tick larvae have six legs, while nymph and adults have eight legs. Black-legged ticks are hard with black shields, called a scutum, on their top sides. The scutum of the adult male tick covers almost the entire the top side of its brown-black body, while the scutum of an adult female tick covers about half of the top side of its orange-red body.

Despite these telling features, ticks are very hard to see. Nymphs are about the size of a poppy seed and adults are about the size of a sesame seed. Because ticks are so tiny, they may easily be mistaken for a freckle or speck of dirt.

CDC

Where do ticks live?

Tick bites that lead to Lyme disease are most common in the spring and summer, when ticks are in the nymph stage. Adult ticks are more active in the fall, but because adults are larger than nymphs, they’re more likely to be noticed and removed. But you or your pet can get a tick bite any time the temperature is above freezing, which is when ticks are active.

Black-legged ticks are most prevalent in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic U.S., from northeastern Virginia to Maine; in North Central states like Wisconsin and Minnesota; and on the West Coast, particularly in northern California.

EL Maloney

What time of year am I most likely to be bitten by a tick?

Tick bites that lead to Lyme disease are most common in the spring and summer, when ticks are in the nymph stage. Adult ticks are more active in the fall, but because adults are larger than nymphs, they’re more likely to be noticed and removed. But you or your pet can get a tick bite any time the temperature is above freezing, which is when ticks are active.

What happens when a tick encounters a human?

Getty Images

Ticks don’t fly or jump, but they do “quest,” meaning they climb up to the edges of grass or shrubs, hold on with their lower legs, and wait with their upper legs outstretched for a person or other animal host to pass by. Ticks can sense the breath of a potential meal from 50 feet away. They can also sense body heat, moisture, and vibrations.

When a host passes by, ticks latch on with their upper legs. Then they look for a good feeding spot. This can be anywhere on the body, but they particularly gravitate to warm, moist areas like the belly button, armpits, or groin. They also often end up in hard-to-see areas like the scalp, behind the ears, and behind the knees.

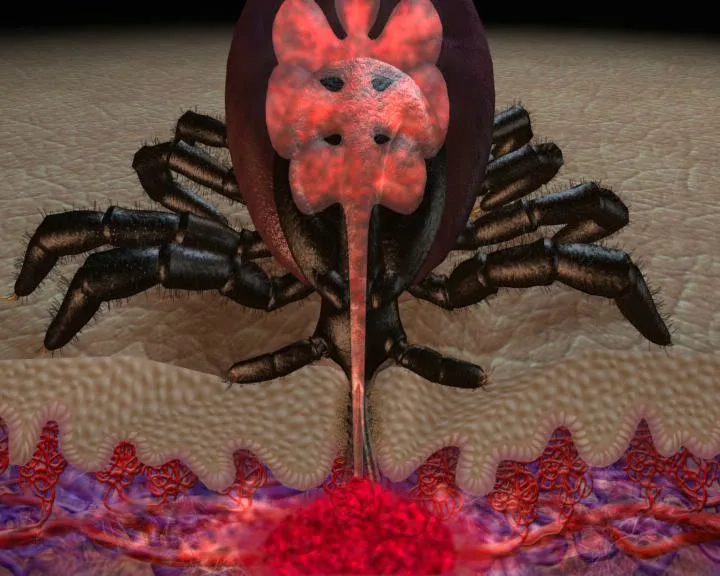

What happens during a tick bite?

When a tick finds a good feeding spot on your body, it grasps your skin with hooks that stick out from its mouth. It uses those hooks to cut into the surface of the skin and hold itself in place. Then it inserts a hollow, straw-like tube that sucks your blood into the tick’s body over the course of several days.

Shutterstock

Lyme Disease Action

Lyme disease bacteria, or other pathogens, can be transmitted to the host while the tick is feeding. The pathogens move from the tick’s gut to the salivary glands, and then pass through the tick’s saliva into the skin.

Ticks have several ways to stay attached and go unnoticed while they feed on your blood. For example, ticks use saliva to form a hardened seal to hold themselves in place for a few days while they feed. Ticks also release a numbing agent in their saliva so that you don’t feel the bite. Tick bites do not hurt, sting, or itch (compare that to a mosquito bite, which begins to itch shortly after the bite.) Elements of tick saliva can also prevent your blood from clotting, which would provide a natural end to the meal, and they interfere with your body’s immune system and its ability to kill off the Lyme disease bacteria. This is why it’s so important to check your body for ticks when you come in from outdoors.

While feeding, a tick’s body will become engorged, or round and full of blood. You may find an engorged or partially engorged tick on your body.

If you don’t find the tick before it finishes feeding, it will drop off when it is done.

Getty Images

If I get a tick bite, does that mean I have Lyme disease?

Not necessarily. Whether or not you will get Lyme disease depends on many factors. For example:

- Was the tick was carrying the Lyme disease bacteria? If you still have the tick, you can have it tested to see what pathogens it was carrying. You can also check with your local health department to see if Lyme disease is common where you live or where you recently traveled. If the answer is yes, it makes it more likely that you were bitten by an infected tick. (For more information, see If You Find a Tick.)

- How long was the tick attached to you? The general rule is that the longer an infected tick has been attached to you, the more likely it is to transmit the Lyme disease bacteria. The CDC says that removing a tick within 24 hours of attachment greatly reduces your chance of getting Lyme disease. Studies show that the chance of getting Lyme disease increases after 48 hours of tick attachment. However, there are documented cases of Lyme disease bacteria being transmitted in less than 24 hours. And if a tick that bites you has already partially fed on another host, it may therefore need to be attached to you for a shorter amount of time to transmit the bacteria.

Any time you get a tick bite, you should call your doctor right away. Don’t wait for symptoms to develop or for the results of a tick test to come back. The best way to prevent Lyme disease after a high-risk bite is with preventive antibiotics. (For more information, see Do I need preventive antibiotics for Lyme disease?)

If you get a tick bite and have symptoms or a rash, then you already have Lyme disease and need to get started on treatment. Talk to your doctor about starting treatment right away, rather than waiting for diagnostic test results. Blood tests for Lyme disease are often negative within the first few weeks after a tick bite, and may be negative in more than 60% of people when they present with early symptoms such as erythema migrans rash.

Can ticks transmit other pathogens in addition to the Lyme disease bacteria?

In addition to the Lyme disease bacteria, black-legged ticks can transmit other pathogens that cause diseases such as babesiosis, anaplasmosis, Powassan virus, ehrlichiosis, and B. miyamotoi disease (hard tick relapsing fever).

Some of these pathogens can be transmitted much faster than the Lyme disease bacteria, which means the tick need only be attached for a short while. For example, the Powassan virus can be transmitted from tick to human in as little as 15 minutes. (For more information, see Other Tick-Borne Diseases.)

Who is at risk for a tick bite?

Everyone who spends time outdoors is at risk for a tick bite. But there are many steps you can take to reduce your risk. For information on how to prevent tick bites on yourself and your pets, see Preventing Tick Bites and Preventing Tick Bites on Pets.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Ticks can be found throughout the United States. The black-legged ticks that spread the Lyme disease bacteria are most prevalent in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic U.S., in North central states like Wisconsin and Minnesota; and on the West coast, particularly in northern California. What’s more, people travel. If you live in an area where black-legged ticks aren’t common — say, South Dakota — but you travel to a place where they are, like Maine, you could get a tick bite while there. If that tick happens to transmit the Lyme disease bacteria to you, you may not develop symptoms until you get back home. In fact, cases of Lyme disease have been reported in all U.S. states except Hawaii.

Children ages 5 to 14 are at highest risk for tick bites, possibly because of how much time they spend playing outside. Check your kids for ticks when they come in from the outdoors. (For more information, see Preventing Tick Bites in Children.)

Outdoor pets are also at risk for a tick bite. Even if a pet is vaccinated against Lyme disease, it can still bring ticks inside, putting you and your loved ones at risk for a tick bite. (For more information, see Preventing Tick Bites on Pets.)

Getty Images

Lyme Disease Outside the U.S.

Lyme disease is also found outside of the U.S., including in Europe and Asia. The ticks that spread Lyme disease on those continents are related to black-legged ticks in the U.S. These ticks carry and transmit different species of Borrelia bacteria, and can cause different Lyme disease symptoms than those that are common in the U.S. If you’ve traveled abroad and suspect you were bitten by a tick or may have picked up Lyme disease on your trip, be sure to let your doctor know where you traveled, because testing for different strains of Borrelia may be necessary.

Myth busters: Ways you cannot get Lyme disease

Here are some ways you cannot get Lyme disease:

- You cannot get Lyme disease from mosquitoes, or from any insects. Only ticks.

- Lyme disease is not contagious. That means you cannot get Lyme disease from touching or kissing, for example.

- You cannot get Lyme disease from a blood transfusion, though the CDC recommends against donating blood if you are being treated for Lyme disease.

Can a pregnant mother pass Lyme disease to her baby?

According to the CDC, transmission of the Lyme disease bacteria from an infected mother to her baby during pregnancy is possible but rare. If you have Lyme disease when you become pregnant or are diagnosed with it while pregnant, tell your obstetrician right away so that you and your doctor can discuss the best treatment options.

1. A brief history of Lyme disease in Connecticut. Connecticut State Department of Public Health website, July 2019.

https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Epidemiology-and-Emerging-Infections/A-Brief-History-of-Lyme-Disease-in-Connecticut

2. Blacklegged (deer) tick. TickEncounter: The University of Rhode Island website.

https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/species/blacklegged-tick/

3. Educational materials. CDC website, March 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/toolkit/index.html

4. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. UpToDate, February 2022.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-of-lyme-disease

5. How many people get Lyme disease? CDC website, January 2021.

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humancases.html

6. How ticks spread disease. CDC website, September 2020.`

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html

7. Identification Guide. TickEncounter: The University of Rhode Island website.

https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/fieldguide/id-guide/

8. Lyme borreliosis: a review of data on transmission time after tick attachment. International Journal of General Medicine, January 2015.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4278789/

9. Lyme disease. CDC website, January 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/

10 Lyme: The First Epidemic of Climate Change by Mary Beth Pfeiffer. Island Press, April 2018.

https://www.thefirstepidemic.com/

11. Pathogen transmission in relation to duration of attachment by Ixodes scapularis ticks. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, March 2018.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29398603/

12. Patient education: Lyme disease symptoms and diagnosis (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate, February 2022.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lyme-disease-symptoms-and-diagnosis-beyond-the-basics

13. Patient education: What to do after a tick bite to prevent Lyme disease (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate, February 2022.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/what-to-do-after-a-tick-bite-to-prevent-lyme-disease-beyond-the-basics

14. Prevent Lyme disease. CDC website, April 2021.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/media/lymedisease.html

15. Prospective study of serologic tests for Lyme disease. Clinical Infectious Diseases, July 2008.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18532885/

16. Tick microbiome: The force within. Trends in Parasitology, July 2015.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25936226/

17. Tickborne diseases of the United States. CDC website, January 2019.

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/

18. Vector-host interactions in disease transmission. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, October 2000.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11075909/