What should I do if I find a tick?

Getty Images

If you find a tick on yourself, your child, or another family member, don’t panic. A tick — or even a tick bite — doesn’t necessarily mean you are going to get Lyme disease or another tick-borne disease. However, you do need to act promptly to remove the tick. The longer a tick is attached, the more time it has to transmit the Lyme disease bacteria and pathogens that cause other disease. Let your doctor know if you are bitten by a tick so you can discuss whether you need preventive antibiotics to prevent Lyme disease.

Ticks are not like mosquitoes, which bite and then fly off. When a tick bites a person, it attaches for several days while it feeds on their blood. A tick attaches to your skin with barbed mouthparts and a cement-like substance, so that it can hold on to you while feeding.

While the tick is attached, it can transmit the bacteria that cause Lyme disease and pathogens that cause other diseases. That’s why, if you find a tick on yourself, you’ll want to remove it as quickly as possible.

You may be able to tell from looking at the tick if it is attached and whether it already bit you.

How can you tell if a tick is attached? When you remove the tick with tweezers, you’ll feel that you’re pulling the tick out of your skin, not just off your skin. Getty Images

If the tick is crawling, that means it’s not attached, but it may have been. A crawling tick could be looking for a good spot to bite, or it might have already bitten you and be finished with its meal.

If the tick is not moving, you’ll know if it’s attached based on a couple of factors:

- When you try to remove the tick, you’ll be able to feel if you’re pulling it out of your skin, versus just off your skin.

- Depending on the size of the tick, you may also be able to see that the tick’s mouth is inside your skin, while the rest of the body is hanging off your skin.

An attached tick may be more difficult to remove.

When a tick feeds, its body becomes engorged, or round and full of blood.

Getty Images

You can’t always tell, but one clue as to whether you’ve already been bitten is to see if the tick is engorged (round and full of blood). Whether or not the tick is engorged or even partially engorged, it is important let your doctor know if you experience any illness after finding a tick on you.

How do I remove a tick?

If possible, before removing the tick, take a photo of it. This might help you and your doctor figure out what type of tick it is and, based on its appearance, the likelihood that it had attached to you and whether it was engorged. If you can’t get a picture, the most important step is removing the tick properly and as quickly as possible.

Attached ticks should be removed with fine-pointed tweezers, though they can also be removed with special tools.

If a tick is not yet attached but is on your skin, hair, or scalp, simply grasp it with tweezers and remove it. Try not to squeeze or crush the tick, as that can make it harder to identify. Once removed, follow steps 3 through 7 below.

To properly remove an attached tick, follow these steps:

- Using tweezers or a tick tool, grab the tick as close to your skin as possible. Try to grab the tick’s head, or directly above the head.

- Keeping the tweezers or tool firmly grasped, slowly pull the tick straight up and out to avoid breaking the tick and leaving part of it in your body. Do not twist. Also, try not to squeeze, crush, or puncture the tick, since its bodily fluids may contain infection-causing pathogens.

- Using the tweezers or tool (not your hands), place the tick inside a zippered plastic bag. It is best to kill the tick, which can be done by placing the zippered bag in the freezer or including an alcohol-based solution (such as hand sanitizer) in the bag.

- Disinfect the bite site with soap and water, or with alcohol or an antiseptic wipe.

- Wash your hands with soap and water.

- Take a photo of the tick in the bag.

- Call your doctor immediately after removing the tick.

Antibiotics to prevent Lyme disease must be given within 72 hours of removing the tick, so the sooner you tell your doctor that you’ve been bitten, the better (for more information, see Do I need preventive antibiotics for Lyme disease?).

Shutterstock

You can remove a tick with fine-tipped tweezers, but some find it is easier to use special tools.

There are several handy tick-removal tools you can purchase like a dual-tipped tweezer such as the Bug Bite Thing Tick Remover or Tick “keys” which provide more leverage and can be kept on a keychain.

If you find a tick and don’t have one of these tools, don’t wait to go buy one. Remove the tick right away with tweezers.

What if the tick breaks apart while I am pulling it out?

If the tick breaks apart while you are pulling it out, try to pull the rest of it out with tweezers, again grabbing as close to your skin as possible. If you cannot fully remove the tick, take a photo of what is left to show to your doctor. They may want you to come in so they can fully remove the tick. If you or your doctor can’t fully remove the tick, it’s okay to leave parts of it in your skin. They will come out as the skin heals. The tick cannot continue to transmit pathogens while only part of it is in your skin, but be aware that it may have already infected you.

What should I NOT do if I notice a tick attached to me?

The following methods are not effective for removing ticks. Some of these methods can actually make it more likely for a tick to infect you.

DO NOT:

- apply Vaseline, nail polish, rubbing alcohol, or kerosene to the tick.

- burn it off with a match or smoldering cigarette.

- scrape the tick off with a card.

- wait for it to fall off.

How can I identify what type of tick it is, and why do I need to know?

Once you have properly removed the tick, you want to identify what type of tick it is. Not all ticks are a threat to humans. Of those that are, there are different types of ticks that carry different pathogens. Identifying the type of tick that bit you will help you and your doctor figure out whether the tick could be carrying the Lyme disease bacteria or pathogens that cause other infections.

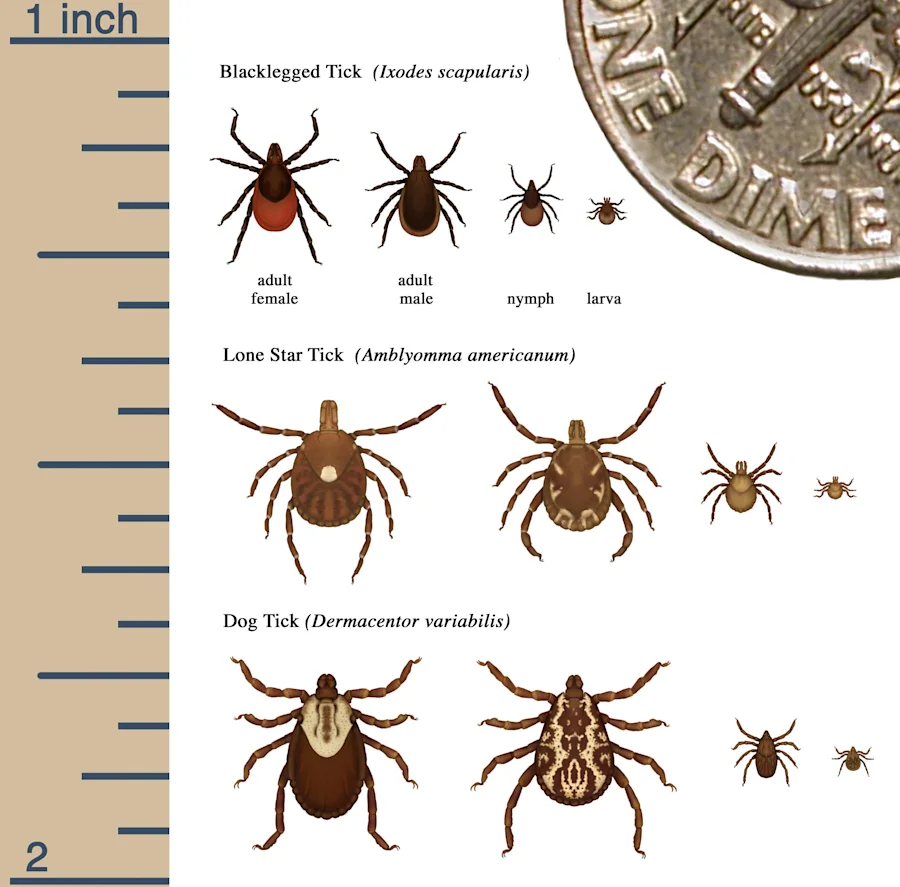

CDC

The ticks that carry Lyme disease are black-legged ticks. These are called Ixodes scapularis in the Eastern U.S., and Ixodes pacificus in the Western U.S. Black-legged ticks are sometimes referred to as deer ticks.

Black-legged ticks go through four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Nymphs and adult female ticks can spread the Lyme disease bacteria to humans. Rarely, larvae, which are microscopic in size, can transmit a cousin of Lyme disease, Borrelia miyamotoi. You may therefore become ill without ever seeing a tick, and should report any unusual symptoms to your doctor after being outside in a high-risk area.

Ticks look different at each life stage. Nymph and adult black-legged ticks have eight legs and are hard-bodied. Male ticks are brown with a black scutum, or shield, that covers most of their body. Female adult ticks have an orange-red body, and their scutum is smaller. The adult females are about one and a half times as large as the adult males.

Tick identification and testing

If you took photos of the tick while it was attached to you or after you removed it, you can send those to your doctor. You can also send photos to TickSpotters from TickEncounter at the University of Rhode Island. They can help you identify the tick.

If you want the tick tested for Lyme and other tick-borne pathogens, put it in a plastic bag and store it in your freezer. Most doctors’ offices cannot test ticks. You can look for labs that specialize in this. Some state public health departments also do this type of testing. Do not wait for results on the tick testing before seeking care from a doctor.

What can I expect when I see my doctor for a tick bite?

If you were bitten by a black-legged tick, your doctor may want to give you preventive antibiotics for Lyme disease before any symptoms appear.

If you already have symptoms or signs of Lyme disease, it’s too late for preventive antibiotics. Instead, you may already have Lyme disease, and a full treatment course of antibiotics (for 10 to 28 days) is warranted. Which antibiotics you take and how long you take them depends on your symptoms.

If your doctor determines that the tick that bit you was not a black-legged tick, watch for symptoms of other tick-borne diseases, and discuss next steps with your doctor. For more information, see Other Tick-Borne Diseases.

Here’s help in answering questions your doctor will ask if you’ve been bitten by a tick.

Only some kinds of ticks are associated with Lyme disease. Black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks, are the ticks that can transmit the Lyme disease bacteria to humans. For more information, see How can I identify what type of tick it is, and why do I need to know?

It may be hard to answer this question, because people do not always notice a tick or tick bite right away. However, you might have a good idea of when the tick bite occurred, such as during a recent outdoor activity.

The general rule is that the longer a tick that carries the Lyme bacteria has been attached to you, the more likely it is that you may get Lyme disease. Removing ticks as quickly as possible is an important step in preventing Lyme disease. And it’s why preventive antibiotics are especially helpful the longer the tick is attached.

Black-legged ticks spread pathogens that cause other diseases, too (such as babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, Borrelia miyamotoi or hard tick relapsing fever, and Powassan virus disease). Tick bites can transmit the pathogens that cause other diseases much faster than they transmit the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. That’s another reason to remove ticks promptly. For more information, see Other Tick-Borne Diseases.

Lyme disease is not confined to New England. This map shows where in the U.S. black-legged ticks have been found.

EL Maloney

Tell your doctor where you were when you were bitten. If you were bitten in a place where Lyme disease is endemic, meaning that the Lyme disease bacteria is regularly found in ticks in that area, preventive antibiotics may be especially important.

The more tick bites you have, the more likely you are to be infected with a pathogen that causes a tick-borne disease. If you get multiple tick bites at once, your doctor is more likely to prescribe preventive antibiotics.

The goal of preventive antibiotics is to cut the chances of infection, and they are given before there is any evidence of infection. As such, the decision to prescribe preventive antibiotics does not depend on symptoms or a positive test.

The preferred antibiotic to prevent Lyme disease in adults is doxycycline.

Do I need preventive antibiotics for Lyme disease?

Getty Images

If your doctor determines that the tick that bit you could have passed the Lyme disease bacteria to your body, taking antibiotics right away (preventive or prophylactic antibiotics) can kill those bacteria before they multiply. This may prevent Lyme disease from developing. If you can prevent Lyme disease after a tick bite, you will also help reduce the chances of short-term illness and potential long-term complications.

Whether or not you need preventive antibiotics depends on several factors, such as:

- the type of tick that bit you

- how long the tick was attached to you and whether it was engorged

- whether Lyme disease is common where you were bitten

- whether you had multiple tick bites at once

All antibiotics can cause side effects. These include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and, rarely, more serious gastrointestinal infection. The risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea may be minimized by using good-quality probiotics.

Why try to prevent Lyme disease?

Without preventive treatment, the Lyme disease bacteria can spread to other parts of the body including the joints, heart, and brain. As the infection spreads through the body over days, weeks, or months, a person might experience a worsening of earlier symptoms or a range of other symptoms. These symptoms may include fatigue and weakness; pain that can come and go and move around the body, including muscle pain, joint pain, and nerve pain, which may be experienced as tingling, numbness, burning, or stabbing sensations; heart palpitations or irregular heartbeat; chest pain; headaches, including migraines; and facial paralysis or drooping of facial muscles (a condition called facial palsy).

Eventually, Lyme disease can cause inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, with “brain fog,” memory, and concentration issues; sleep disturbances; a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including but not limited to depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and psychosis; and debilitating fatigue. (For more on stages and associated symptoms of Lyme disease, see Stages and Symptoms of Lyme Disease.)

Current guidelines suggest that a single 200-milligram (mg) dose of doxycycline is appropriate for preventing Lyme disease after a high-risk tick bite. This should be taken within 72 hours of tick removal following a high-risk bite. A tick bite is considered to be high-risk if:

- the bite was from a black-legged tick

- the bite occurred in a highly endemic area (a place where ticks regularly carry the Lyme disease bacteria), and

- the tick was attached for more than 36 hours.

This is the recommendation in the 2020 Lyme disease guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). However, the ideal preventive treatment, dose, and duration are uncertain. Additional research is needed to confirm the best approach.

Single-dose doxycycline is not recommended to prevent other tick-borne illnesses. According to the CDC, there is no evidence to show this works. For more information on co-infections and their symptoms, see Other Tick-Borne Diseases.

Some doctors prescribe a 10-to-20-day course of doxycycline (two times per day) to prevent Lyme disease. This is similar to the course they would use to treat an early, established Lyme infection. The longer course recommendation is included in the 2014 guidelines published by the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS).

Let your doctor know if you experience symptoms associated with Lyme disease even after taking preventive antibiotics. For more information, see Stages and Symptoms.

1. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention against Lyme disease following tick bite: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, November 2021.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34749665/

2. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clinical Infectious Diseases, January 2021.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33251700/

3. Evaluation of a tick bite for possible Lyme disease. UpToDate. February 2022,

https://www.uptodate.com

4. Evidence assessments and guideline recommendations in Lyme disease: the clinical management of known tick bites, erythema migrans rashes and persistent disease. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy, July 2014.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077519/

5. How to remove a tick. TickEncounter: The University of Rhode Island website.

https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/how-to-remove-a-tick/

6. Lyme disease. CDC website, January 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/

7. Pathogen transmission in relation to duration of attachment by Ixodes scapularis ticks. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, March 2018.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29398603/

8. Patient education: What to do after a tick bite to prevent Lyme disease (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate, February 2022.

https://www.uptodate.com

9. Prevent Lyme disease. CDC website, April 2021.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/media/lymedisease.html

10. Ticks. CDC website, October 2021.

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/